Syrians returning home face the deadly threat of landmines

Idlib, Syria

BBC

BBCAyghad never imagined that his dream of returning to his farm could turn into a nightmare.

Fighting back tears, he shows us a photo of his late father, smiling and surrounded by the abundant olive trees on his land in the Idlib province of northwestern Syria.

The photo was taken five years ago, a few months before forces allied with the former government captured their village near the city of Saraqeb.

The city was for years a strategic stronghold for Syrian opposition factions, before forces allied with the fallen regime of Bashar al-Assad launched an offensive against rebels in Idlib province in late 2019.

Hundreds of thousands of residents fled their homes as Assad forces captured several other rebel strongholds in the northwest in early 2020.

Ayghad and his father were also among the displaced people.

“We had to leave because of the fighting and the airstrikes,” says Ayghad, tears in his eyes. “My father was refusing to go. He wanted to die on his own soil.”

From then on, father and son were eager to return. And when opposition forces recaptured his village in November 2024, his dream was about to come true. But disaster soon struck.

“We went to our land to harvest some olives,” Ayghad explains. “We went in two different cars. My father took a different route back to our home in Idlib city. I warned him against it, but he insisted. His car hit a landmine and exploded. Went.”

Ayghad’s father died at the scene. That day he not only lost his father but also lost his family’s main source of income. His farm, spread over 100,000 square meters, was filled with 50-year-old olive trees. It has now been designated a hazardous mine area.

At least 27 people, including children, have been killed by landmines and unexploded remains of war since the fall of Bashar al-Assad’s regime in early December, according to Hello Trust, an international organization specializing in clearing landmines and other explosive devices. At least 144 people have died.

The Syrian Civil Defense – known as the White Helmets – told the BBC that many of those killed were farmers and landowners trying to return to their land after the fall of the Assad regime.

Unexploded remains of war pose a serious threat to life in Syria. These are mainly divided into two categories. The first are unexploded ordnance (UXO) such as cluster bombs, mortars and grenades.

Hassan Talfa, who heads the White Helmets team clearing UXO in northwestern Syria, explains that clearing these devices is less challenging because they are usually visible above ground.

The White Helmets say that, between November 27 and January 3, they cleared about 822 UXOs in northwestern Syria.

The bigger challenge, Mr Talfa says, lies in another category of munition – landmines. He explains that former government forces planted thousands of trees in various areas of Syria – mainly on agricultural land.

According to the White Helmets, most of the deaths recorded since the fall of the Assad regime occurred on former war frontlines. Most of those killed were men.

Mr. Talfa took us to two huge fields filled with landmines. Our car followed him down a long, narrow and winding dirt road. This is the only safe way to reach the fields.

Children run along the side of the road. Hassan tells us that they are from families who have recently returned. But the dangers of the mines surround them.

As we get out of the car, he points to a barrier in the distance.

“It was the last point separating areas in Idlib province controlled by government forces from areas held by opposition groups,” he tells us.

He says Assad forces planted thousands of mines in fields across the barrier to prevent rebel forces from advancing.

The fields around where we are standing were once important agricultural lands. Today, they are all barren, with no greenery visible except the green tops of the landmines that we can see with binoculars.

With no expertise in clearing landmines, the White Helmets can currently only cordon off these areas, and remove signs warning people on their borders.

They also spray-paint dirt barriers around the edges of fields and warning messages on homes. They read, “Danger – there are landmines ahead.”

They lead campaigns to raise awareness among local people about the dangers of logging into contaminated land.

While returning we meet a 30 year old farmer who has recently returned. He tells us that some of the land belongs to his family.

“We couldn’t recognize any of it,” says Mohammed. “We used to grow wheat, barley, cumin and cotton. Now we can’t do anything. And unless we can cultivate these lands, we will always be in a bad economic condition,” he says, clearly disappointed.

The White Helmets say they have identified and defused about 117 landmines in just one month.

They are not the only ones working to clean up the mines and UXO, but there seems to be little coordination between the efforts of the different organizations.

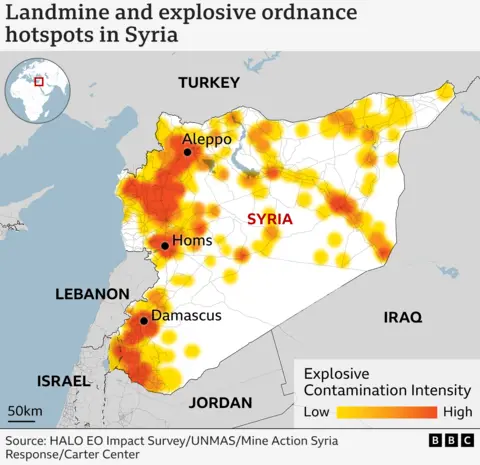

There are no accurate statistics for areas contaminated by UXO or landmines. But international organizations like Hello Trust have prepared approximate maps.

Damien O’Brien, program manager for Hello Syria, says a comprehensive survey needs to be conducted to understand the scale of pollution in the country. They estimate that approximately one million devices would need to be destroyed to protect civilian lives in Syria.

“It’s quite likely that there will be some landmines laid around any Syrian army positions as a defensive technology,” Mr O’Brien says.

“In places like Homs and Hama, there are entire neighborhoods that have been almost completely destroyed. Anyone who is going to evaluate those structures, for demolition or to rebuild them, needs to be aware of this. “There has to be a possibility that there could be unexploded ordnance there as well, whether it’s bullets, cluster munitions, grenades, shells.”

BBC News

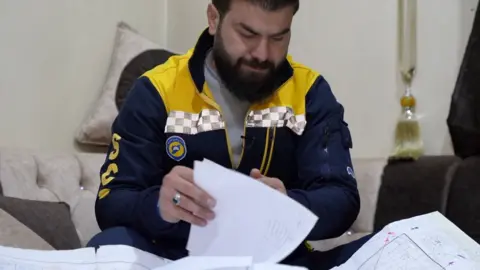

BBC NewsThe White Helmets found a treasure that could aid efforts to clear the mines. In his office in the city of Idlib, Mr Talfa shows us stacks of maps and documents left behind by government forces.

They show the locations, numbers and types of mines planted in different areas in north-western Syria.

“We will hand over these documents to the bodies that deal directly with landmines,” says Mr Talfah.

But the local expertise currently available in Syria does not appear to be sufficient to deal with the serious threats posed to civilian life by unexploded weapons.

Mr O’Brien emphasizes that the international community needs to work closely with the new government in Syria to improve expertise in the country.

“We need money from donors to be able to expand our capacity, which means employing more people, buying more machines and operating in a wider area,” he says.

As far as Mr. Talfa is concerned, cleaning up UXOs and raising awareness of their dangers has become a personal mission. Ten years earlier, he had lost his leg while clearing a cluster bomb.

He says his injury and the heartbreaking events of children and civilians affected by UXO have fueled his determination to keep working.

“I never want any civilian or team member to go through what I went through,” he says.

“I can’t describe the feeling I get when I remove a threat that endangers the lives of civilians.”

But unless international and local efforts are coordinated to neutralize the threat of landmines, the lives of many civilians, especially children, will remain at risk.