India’s leading female anthropologist who challenged Nazi race theories

Urmila Deshpande

Urmila DeshpandeIrawati Karve lived a life that was different from those around her.

Born in British-ruled India, and at a time when women did not have many rights or freedom, Karve did the unthinkable: she pursued higher studies in a foreign country, becoming a college professor and India’s first female anthropologist.

She also married the man of her choice, went swimming in a bathing suit, rode a scooter, and even had the courage to refute the racist hypothesis of her doctoral supervisor – a famous German anthropologist named Eugen Fischer.

His writings on Indian culture and civilization and its caste system are ground-breaking, and form part of the curriculum in Indian colleges. Yet she remains an obscure figure in history and much about her life remains unknown.

A new book titled Iru: The Remarkable Life of Iravati Karve, written by her granddaughter Urmila Deshpande and academic Thiago Pinto Barbosa, sheds light on her fascinating life, and the many obstacles she overcame to pave an inspiring path for women and men . Who came after him.

Born in Burma (now Myanmar) in 1905, Irawati was named after the Irrawaddy River. The only girl among six siblings, her family loved her and brought her up comfortably.

But the young girl’s life took unexpected turns, resulting in experiences that shaped her as a person. In addition to strong women, Irawati’s life was also filled with empathetic, progressive men who paved the way for her to break barriers and cheered her on as she did so.

At the age of seven, Irawati was sent to boarding school in Pune – a rare occasion by her father when most girls were forced into marriage. In Pune he met RP Paranjape, a prominent educationist, whose family informally adopted Irawati and raised her as their own.

In the Paranjape Gharana, Irawati was exposed to a way of life that celebrated critical thinking and religious life, even if it meant going against Indian society. Paranjape, whom Irawati fondly called “Appa” or her “second father”, was a man far ahead of his time.

Urmila Deshpande

Urmila DeshpandeA college principal and staunch supporter of women’s education, he was also an atheist. Through them, Irawati discovered the fascinating world of social science and its impact on society.

When Irawati decided to pursue a doctorate in anthropology in Berlin, despite her biological father’s objections, she received support from Paranjape and her husband, Dinkar Karve, a science professor.

After a several-day long journey by ship, she arrived in the German city in 1927 and began pursuing her degree under the mentorship of Fischer, a renowned professor of anthropology and eugenics.

At the time, Germany was still reeling from the effects of World War I and Hitler had not yet come to power. But the specter of anti-Semitism was beginning to raise its ugly head. Irawati witnessed this hatred when one day she learned that a Jewish student had been murdered in her building.

In the book, the authors describe the fear, shock and disgust that Irawati felt when she saw a man’s body lying on the sidewalk outside her building, bleeding on the concrete.

Irawati had to grapple with these feelings while working on a thesis assigned by Fischer: to prove that white Europeans were more logical and reasonable—and therefore racially superior—to non-white Europeans. It involved the careful study and measurement of 149 human skulls.

Fischer hypothesized that white Europeans had asymmetric skulls to accommodate larger right frontal lobes, which allegedly symbolized higher intelligence. However, Irawati’s research found no association between race and skull asymmetry.

“He certainly refuted Fisher’s hypothesis, but he also refuted the principles of that institution and the mainstream theories of the time,” the authors write in the book.

He boldly presented his findings, incurring the displeasure of his mentor and jeopardizing his degree. Fisher gave him the lowest grade, but his research critically and scientifically rejected the use of human differences to justify discrimination. (Later, the Nazis used Fischer’s theories of racial superiority to further their agenda, and Fischer joined the Nazi Party.)

Urmila Deshpande

Urmila DeshpandeThroughout her life, Irawati demonstrated this attitude of courage along with endless empathy, especially for the women she encountered.

At a time when it was unthinkable for a woman to travel far from home, Irawati went on a trip to remote villages of India after returning to the country, sometimes with her male colleagues, sometimes with her students and even Even with your children. , To study the life of different tribes.

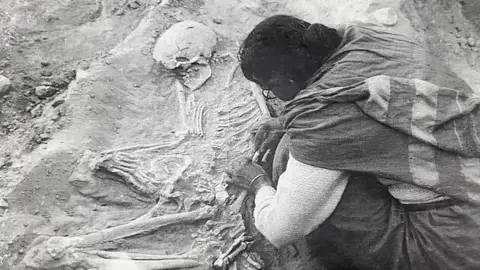

She joined archaeological expeditions to recover 15,000-year-old bones, connecting the past and present. These arduous journeys took them through forests and rugged terrain for weeks or months, with the book describing them sleeping in barns or truck beds and often spending days with little food.

Irawati also bravely faced social and personal prejudices while interacting with people from all walks of life.

The author describes how Irawati, a Chitpavan Brahmin from the traditionally vegetarian upper caste Hindu community, bravely ate partially raw meat offered to her by a tribal leader whom she wanted to study. They recognized it as a sign of friendship and a test of loyalty, responding with openness and curiosity.

His studies fostered a deep empathy for humanity, which later led him to criticize fundamentalism in all religions, including Hinduism. He believed that India belonged to all who called it home.

The book describes the moment when, reflecting on the terror inflicted on the Jews by the Nazis, Irawati’s mind wandered to a shocking realization that forever changed her view of humanity.

“In these reflections, Irawati learns the hardest lesson from Hindu philosophy: that all you are, too,” writes the author.

Irawati died in 1970, but his legacy lives on through his work and the people he inspired.