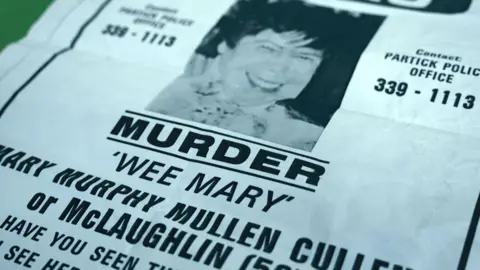

How a cigarette butt helped solve a 30-year-old murder mystery

crown office

crown officeA cigarette stub recovered from Mary McLaughlin’s flat has provided the first clue to the identity of her killer – more than 30 years after she was strangled.

A matching DNA profile was later found hidden in a knot of rope from the dressing gown used to murder the mother of eleven.

The breakthrough initially stunned cold case detectives as the prime suspect was a prisoner in Edinburgh when 58-year-old Mary was found dead in the west end of Glasgow.

But the governor’s log book confirmed that serial sex offender Graham McGill was on parole at the time the grandmother was murdered.

And it revealed that within hours of leaving Mary’s house in the early hours of September 27, 1984, he returned to his cell.

firecrest

firecrestA new BBC documentary, Murder Case: The Hunt for Mary McLaughlin’s KillerTells the story of the cold case investigation – as well as the devastating impact the murder has on Mary’s family.

Senior forensic scientist Joan Cochrane said: “There are some murders that stay with you.

“Mary’s murder is one of the more disturbing cold cases I have dealt with.”

Mary spent her last night drinking and playing dominoes in the Hyland pub, now the Duck Club, which overlooks Mansfield Park.

She walked alone from the bar on Hyndland Street, less than a mile, to her flat between 22:15 and 22:30.

On the way she stopped at Armando’s chip shop on Dumbarton Road, where she joked with the staff while buying dumplings and cigarettes.

A taxi driver, who knew her as Wei Mei, later described how he saw a single man following her as she walked down the street barefoot with her shoes on.

firecrest

firecrestThe sequence of events that led to McGill arriving at Mary’s third-floor flat in Crathy Court is unknown, but there was no sign of forced entry.

As soon as he went inside, he brutally attacked a woman who was more than twice his age.

In the age before mobile phones, Mary was not in constant touch with her large family living in Glasgow, Lanarkshire and Ayrshire.

Once a week one of his sons, Martin Cullen, came to visit him.

But when the then 24-year-old came to the flat on October 2, 1984, there was no answer and when he opened the letterbox there was a “horrible smell”.

Inside, Mary was found dead, lying on her back on a bare mattress.

Her false teeth were on the floor and a new green dress that she had worn to the pub was placed back to front.

Former senior investigating officer Ian Wishart described the crime scene as “particularly brutal”.

He added, “The sad thing is that she must have been looking into his eyes when he committed the murder.”

The post-mortem examination concluded that Mary had died by strangulation at least five days earlier.

crown office

crown officeDetectives collected more than 1,000 statements in the months that followed, but the search for Mary’s killer hit several dead ends.

The following year the family were told the investigation had been closed but a CID officer urged Mary’s daughter Gina McGuigan: “Don’t lose hope.”

Joanne Cochrane was working at the Scottish Crime Campus in Gartcosh, North Lanarkshire, when she was asked to review evidence from the scene that had been preserved in paper bags for 30 years.

“They didn’t know about DNA profiling at that time,” he said.

“He had no idea of the possibilities inherent in these objects.

“They couldn’t possibly know the value it would have had.”

Ms Cochrane said the original investigation team showed “amazing foresight” in preserving evidence, including cigarette ends.

Google

GoogleMary had 11 children from two fathers and was well known in the local community.

But daughter Gina revealed in the documentary that there was tension because he had abandoned his first six children and left five of his children with another partner.

She said: “I thought there was a hidden killer within the family.”

Gina, who wrote a book about her mother’s murder, said she shared her suspicions with the police.

He further said, “My brothers and sisters were thinking the same way as me in 1984.

“It was one of his own children who was involved or knew something but we couldn’t prove anything.”

By 2008 four separate reviews failed to provide a profile of the suspect.

The fifth review was initiated in 2014 and ultimately led to a breakthrough New DNA-profiling feature At the Scottish Crime Campus.

Previously experts could see 11 individual DNA markers but the latest technology is able to identify 24.

This dramatically increased the chances for scientists to obtain results from small or low-quality samples.

Tom Nelson, forensic director of the Scottish Police Authority, said in 2015 that the technology would “make it possible to reach back in time, as well as have the potential to rekindle justice for those who have given up hope”.

Samples collected in 1984 included locks of Mary’s hair and nail fragments.

But the breakthrough came from the end of an Embassy cigarette sitting on the ashtray on the coffee table in the living room.

This was of particular interest to the Cold Case team because Mary’s favorite brand was Woodbine.

Ms Cochrane said she hoped technological advances would enable them to obtain trace levels of DNA.

He explained in the documentary: “Then we get this eureka moment, our eureka moment, where the end of the cigarette, which previously didn’t give us a DNA profile, is now giving us the full male profile.

“This is something we’ve never had before and it’s the first obviously significant piece of forensic science in the case.”

It was sent to the Scottish DNA database and compared to thousands of profiles of convicted criminals.

The results were sent to Ms Cochrane in a form via email.

She quickly scrolled down and saw a cross next to the box: “Direct Match”.

The expert said: “It was a truly hair-raising moment.

“It identifies a man called Graham McGill and on the form that came back to me I can see that he has a serious conviction for sexual offences.

“After more than 30 years we had a person who matched that DNA profile.”

police scotland

police scotlandBut the long-awaited success created a puzzle when it emerged that McGill – who had been convicted of rape and attempted rape – was a prisoner at the time of Mary’s murder.

Records also revealed that she was not released until October 5, 1984 – nine days after the grandmother was last seen alive.

Former Debt Superintendent Kenny McCubbin was tasked with solving a mystery that made no sense.

Ms Cochrane was also told that more forensic evidence was needed to build a solid case.

That search led him to another “time capsule of DNA” – the cord from the dressing gown that was used to strangle Mary.

Ms Cochrane believed it was highly likely that the person who had tightened the knot would have touched the material hidden in it.

Under the glare of fluorescent lights in his laboratory he slowly opened it piece by piece to expose the fabric for the first time in more than three decades.

She said: “We found the key piece of evidence – DNA matching Graham McGill – on lumps inside the ligature.

“He tied that noose around Mary’s neck and tied those knots to strangle Mary.”

firecrest

firecrestSeparately, traces of McGill’s semen were also found on the grandmother’s green dress.

But Det Superintendent McCubbin, now retired, said in the documentary that forensic evidence alone was not enough to ensure a conviction.

He said: “It doesn’t matter what our DNA is.

“He has the perfect alibi. How could he commit murder if he was in prison?”

The records were difficult to find because HMP Edinburgh was being rebuilt at the time of the murder and in the age before computers, the paperwork was lost.

Mr McCubbin’s search eventually led him to the National Records of Scotland in the heart of Edinburgh, where he tracked down the governor’s journals.

And a single entry changed everything.

Next to the jail number was the name “G McGill” and the abbreviation “TFF”.

Mr McCubbin said: “That was training for independence, which meant home leave at the weekend.”

The investigation team found that McGill was on two-day weekend leave, with three days of pre-parole leave added, and returned to prison on September 27, 1984.

Former senior investigating officer Mark Henderson said: “That was the nugget of gold we were looking for.”

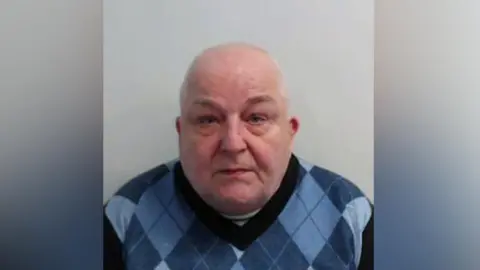

McGill was eventually arrested on 4 December 2019.

At the time he was still being managed as a sex offender, but was working as a fabricator for a company based in Linwood, Renfrewshire, in the Glasgow area.

Gina said the news was a relief and added, “I never thought I’d see this in my lifetime.”

McGill was ultimately found guilty after a four-day trial in April 2021 and sentenced to a minimum of 14 years in prison.

The judge, Lord Burns, told the High Court in Glasgow that McGill was 22 when he strangled Mary, but in the dock he stood as a 59-year-old.

He added: “Her family had to wait that whole time to find out who was responsible for that act, knowing that whoever did it was probably at large in the community.

“He never gave up hope that someday he would find out what had happened to him.”