‘Hero’ ship that fixes Africa’s internet blackouts – BBC gets ride

BBC News, Acra

BBC

BBCCrew by more than 50 engineers and technicians, a ship of a football field, cruel the oceans around Africa to keep the continent online.

This provides an important service, as last year’s Internet Blackout showed that when deep buried internet cables under the sea were damaged.

Millions of digital drowned in darkness from Lagos to Nairobi: The messaging app crashed and banking transactions failed. This struggled with businesses and individuals.

This loan was Thavanin which fixed many cable failures. The ship, where a BBC team has recently spent a week on the banks of Ghana, has been doing this special repair work for the last 13 years.

“Because of me, the country remains connected,” tells the BBC, a cable join from South Africa, Shuru, Arndase, who has been working on a ship for more than a decade.

“This is the work of people at home because I bring the main feed,” they say.

“You have a hero who save life – I am a hero because I save communication.”

His pride and passion reflects the spirit of the efficient crew on Leon Thavanin, which is eight floors high and a classification of equipment.

Internet is a network of computer server – to read this article it is likely that one of at least 600 fiber optic cables worldwide collected data to present it on its screen.

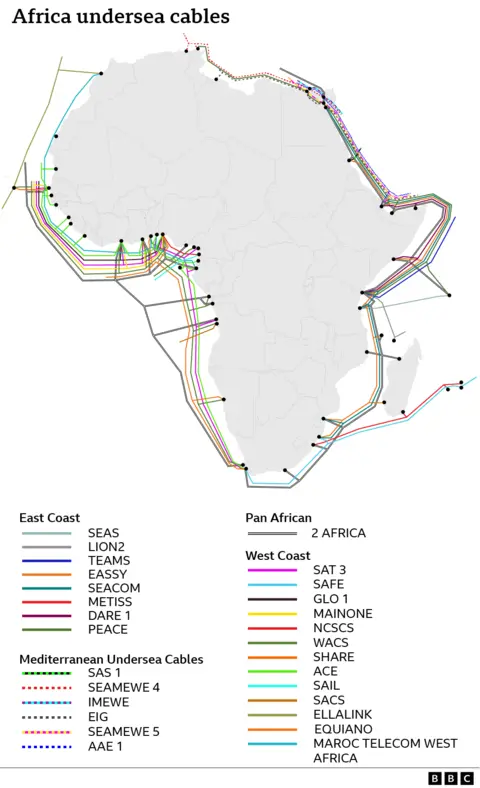

Most of these servers are in data centers outside Africa and fiber optic cables run along the ocean floor that connects them with coastal cities on the continent.

The data-split fiberglass travels through the wires, which is often grouped in the pairs and protected by various layers of plastic and copper, which depends on how close the cables are.

“As long as the servers are not in the country, you need a connection. A cable runs from one country to another, connects users to the server storing its data – whether it is reaching Facebook or any other online service,” Benjamin Smith, “Says Benjamin Smith, Deputy Chief of Mission.

Undercris fiber optic cable is designed to work for 25 years with minimal maintenance, but when they are damaged, it is usually caused by human activity.

“The cable usually does not break on its own until you are in the area where there are too much streams and very sharp rocks,” Charles Held, who is in charge of the ship -operated vehicle (ROV).

“But most of the time these people anchoring, where they should not do and sometimes scrape the travelers with a seabed to fish, so we will usually see traces from the tritting.”

Mr. Smith also says that natural disasters damage cables, especially with extreme weather conditions in parts of the continent. He gives an example of seas away from the banks of the Democratic Republic of Congo, where the Congo river is emptied in the Atlantic.

“In the Congo Valley, where they have too much rainfall and low tide, it can create streams that damage the cable,” they say.

It is difficult to intentionally identify the sabotage – but Leon Thavanin Crew says he did not see any clear evidence of himself.

A year ago, three important cables in Red C – CCom, AAE -1 and EIG – It was reportedly dissected by an anchor of a shipDisrupting connectivity for millions of people in East Africa including Kenya, Tanzania, Uganda and Mozambique.

Just one month later, in March 2024, a separate set of brakes in WACS, ACE, Sat-3, and cables on the coast of West Africa crossed severe internet blackouts Nigeria, Ghana, Ivory Coast and Liberia,

Anything that was necessary for the Internet to function feels stress because the repair extended for weeks.

Then in May, still another blow: Seacom and Eassy cables were damaged from the coast of South Africa, once again hit connectivity in many East African countries.

Such defects are detected through the cables of power and signal strength.

“A cable can have 3,000 volts and suddenly it falls up to 50 volts, which means a problem,” the mission’s head says Loik Walrand, the major of the ship’s ship.

There are local teams with ability to deal with defects in shallow water, but if they are found beyond a depth of 50 meters (164 ft), the ship is called in action. Its crew can fix more than 5,000 meters of cables above sea level.

It took a week to deal with the repair seen by the BBC of Ghana, but most internet users did not notice as the traffic was redirected to another cable.

The nature of every repair depends on the part of the cable that is damaged.

If the fiberglass breaks in the core, it means that the data cannot travel with the network and needs to be sent to another cable.

But some African countries have only a cable that are serving them. This means that a cable damaged in this way leaves the affected area without internet.

At other times, the protective layers of fiber may be damaged, which means that data transmission still occurs, but with low efficiency. In both cases, the crew will have to find an exact location of damage.

In the case of broken fiber filament, a mild sign is sent through the cable and through its reflection, the crew can determine where the brake is.

When the problem is accompanied by insulation of cable – known as “shunt fault” – it becomes more complex and an electrical signal with cable should be sent to track physically where it is lost.

After reducing the potential area for mistake, the operation moves to the ROV team.

Built like a bulldozer, the ROV, which weighs 9.5 tons, is lowered under the water where it is directed below on the sea floor.

Around five crew members work with a crane operator to deploy it – once it is released from its harness, it is called the navel cord, it floats by grace.

“It does not sink,” says Mr. Held, stating how it uses four horizontal and vertical thrusters to move in any direction.

The three cameras of the Rov allow the ships to find the exact location of the defects as it goes to the sea bed.

Once found, Rov bites the affected part using its two arms, then connects it to a rope that is pulled back to the ship.

Here the defective section is separated and included in a new cable and included in a new cable – a procedure that looks like welding and which takes 24 hours in terms of operation seen by the BBC.

The cable was later carefully launched to the sea bed and then the ROV made a final journey to inspect it that it was kept well and the coordinates were taken to update the map.

When an alert is obtained about a damaged cable, the loan Thavanin crew is ready to raise within 24 hours. However, their response time depends on several factors: the location of the ship, availability of additional cables and bureaucracy challenges.

“The permits may take weeks. Sometimes we go to the affected country and the paperwork until then makes up the apartay,” Sri Walrand says.

On average, the crew spends more than six months in the sea every year.

“This is part of the job,” Captain Thomas Quhehek says.

But while talking to the crew members amidst the tasks, it is difficult to ignore their personal sacrifices.

They are prepared from various backgrounds and nationalities: French, South African, Filipino, Malagasi and more.

The ship’s chief steward Adrian Morgan has missed the anniversary of five consecutive wedding from South Africa.

“I wanted to leave. It was difficult to stay away from my family, but my wife encouraged me. I do this for them,” they say.

Another South African, maintenance Fitter Noel Goyman, is worried that he may recall his son’s marriage in a few weeks if the ship is called to another mission.

“I heard that we can go to Durban (in South Africa). My son is going to be very sad because he does not have a mother,” says Mr. Goaimiman, who lost his wife three years ago.

“But I am retiring in six months,” he combines with a smile.

Despite the emotional toll, the ship has a cameradered.

When off-duty, crew members are either playing video games in the lounge or sharing food in the mess hall of the ship.

His entry into the profession is diverse like his background.

Whereas Mr. Goeman moved to the sea to escape the life of his father, following his father’s footsteps, South African Remeario Smith.

“When I was younger, I was involved in the gang,” Mr. Smith says, “When I turned 25, my child was born, and I knew I had to change my life.”

Like others, he appreciates the role that the ship plays on the continent.

“We are the link between Africa and the world,” says Chief Engineer Pheron Hartzenberg.

Additional reporting by Jess Orbach Jahazehh.

You may also be interested in:

Getty Image/BBC

Getty Image/BBC