‘Doors are open to IS’ – Syrian Kurds warn as Turkish-backed forces advance

BBC/Michael Steininger

BBC/Michael SteiningerAs the new Syria struggles to take shape, old threats are reemerging.

The chaos since the overthrow of Bashar al-Assad is “paving the way” for a comeback for the so-called Islamic State (IS), according to a key Kurdish commander who helped defeat the jihadist group in Syria in 2019. The withdrawal has started.

According to General Mazloum Abdi, commander of the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF), a predominantly US-backed Kurdish militia coalition, “Daesh (IS) activities have increased significantly and the threat of resurgence has doubled.” “They have more capabilities and more opportunities.”

He says that according to intelligence reports, IS militants have seized some weapons and ammunition left by Syrian regime troops.

And he warned that there is a “real danger” that militants will try to break out of SDF-run prisons in north-east Syria, which hold about 10,000 of their people. The SDF has also kept about 50,000 of his family members in camps.

Our interview with the General took place late at night, at a location we cannot disclose.

He welcomed the fall of the Assad regime – which detained him four times. But he seemed tired and frustrated at the prospect of fighting old battles once again.

“We fought against them (IS) and killed 12,000 people,” he said, referring to SDF losses. “I think at some level we have to get back to where we were before.”

He says the risk of IS’s resurgence has increased as the SDF comes under increasing attack from neighboring Turkey and rebel groups it supports and will have to divert some fighters to that fight. He tells us that the SDF has had to halt counter-terrorism operations against IS, and hundreds of thousands of prison guards have returned home to defend their villages.

Ankara views the SDF as an extension of the PKK – outlawed Kurdish separatists who have waged an insurgency for decades, and are classified as terrorists by the US and EU. He has long wanted a 30 km “buffer zone” in the Kurdish region in northeastern Syria. Since the fall of Assad, he has been making more efforts to achieve this.

General Abdi said, “The number one threat now is Türkiye because its airstrikes are killing our forces.” “These attacks must stop, as they are distracting us from focusing on the security of the detention centres,” he said, “although we will always do our best.”

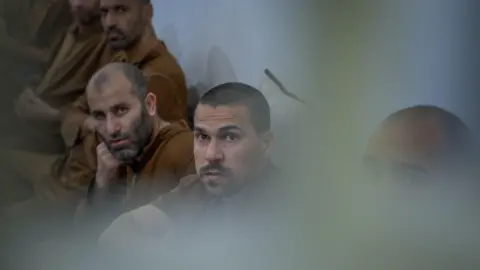

Inside al-Sina, the largest prison for IS detainees, we saw layers of security and felt the tension among the staff.

The former educational institution in the town of al-Hasakah houses about 5,000 men – suspected IS fighters or supporters.

BBC/Michael Steininger

BBC/Michael SteiningerThe door of each cell is locked and secured with three bolts. The corridors are divided into sections by heavy iron gates. The guards are masked and have batons in their hands. It is rare to reach here.

We were allowed a glimpse inside two cells but could not talk to the people inside. They were told that we were journalists and were given the option to hide our faces. Some did. Most sat quietly on blankets and thin mattresses. Two men were walking quickly on the floor.

Kurdish security sources say most of the prisoners in al-Sina were with IS until its last stand and were deeply committed to its ideology.

We were taken to meet a 28-year-old detainee – thin and soft-spoken – who did not want to give his name. He said that he is speaking openly, although he will not say much on major issues.

BBC/Michael Steininger

BBC/Michael SteiningerHe told us that he left his native Australia at the age of 19 to visit his grandmother in Cyprus.

“From there, one thing led to another,” he said, “and I ended up in Aleppo.” He claimed he was working with an NGO in Raqqa city when IS captured it.

I asked whether he had blood on his hands and whether he was involved in murdering anyone? “No, I wasn’t,” he replied, barely audible.

And did he support what IS was doing? He replied, “I don’t want to answer that question because it might affect my case.”

He hopes to return to Australia one day, although he is unsure whether he will be welcomed.

There is also hope behind the wire at Rose Camp – about a three-hour drive away – that freedom is coming. somehow.

This bleak expanse of tents – surrounded by walls, fences and watch towers – is home to approximately 3,000 women and children. They have never been prosecuted or convicted but are families of IS fighters and supporters.

There are many British women in the camp. We met three of them briefly. All said their lawyers had asked them not to speak.

In a windswept corner we met a woman eager to talk – Saida Temirbulatova, 47, a former tax inspector from Dagestan. His nine-year-old son Ali was standing silently beside him. They hope that overthrowing Assad will mean freedom for both of them.

BBC/Michael Steininger

BBC/Michael Steininger“The new leader Ahmed al-Sharaa (head of the Islamic group Hayat Tahrir al-Sham) gave an address, saying he would give everyone their freedom. We also want freedom. We want to leave, most likely. “For Russia. It’s the only country that will take us.”

The camp manager told us that others believed that IS would come to their rescue and disarm them. He asked us not to use his name because he fears for his safety.

“The camp has been quiet since the fall of Assad. Usually, when it’s this quiet, it means women are organizing themselves,” she said. “They have packed their bags to leave. They say: ‘We will soon move out of this camp and renew ourselves. We will come back again as IS.'”

She says a visible change is visible, even among children, who shout slogans and abuse passers-by. “They say: ‘We will come back and get you. It (IS) is coming soon.'”

During our time at the camp many children raised the index finger of their right hand. This gesture is used by all Muslims in daily prayers, but it is also widely used by IS terrorists in propaganda images.

The women of Rose Camp are not the only ones packing their bags.

Some Kurdish civilians in the city of al-Hasakah are doing the same – fearing a return of jihadists and another ground offensive by Turkey in north-eastern Syria.

Jevan, 24, who teaches English, is reluctantly getting ready to leave.

“I have packed my bag and am preparing my ID and important documents,” he told me. “I don’t want to leave my home and my memories, but we all live in a state of constant fear. The Turks are threatening us, and the doors are open to IS. They can attack their prisons. They can do anything. They can do it if they want.”

At the beginning of the Syrian civil war in 2011, the soldier had been displaced from the northwestern city of Aleppo once before. He is wondering where to go this time.

“The situation demands immediate international intervention to protect civilians,” he says, and I ask whether he thinks it will come. “No,” he replies softly. But he asks me to state my argument.

Additional reporting by Michael Steininger and Matthew Goddard