UK radioactive plutonium to dispose of stockpile

Science Correspondent, BBC News

Getty images

Getty imagesThe government says it will settle its 140 tonnes of radioactive plutonium – currently stored in a safe feature in Sellafield in Cumbria.

The world’s largest reserves in the UK are the world’s largest reserves, a product of nuclear fuel renovation.

It has been placed on the site and has been accumulating in a form for decades that will allow it to be recycled in the new nuclear fuel.

But the government has now decided that it will not be reused and instead states that it wants to keep the dangerous material “beyond access” and is designed for permanent disposal which is deep underground.

Kevin Church, BBC

Kevin Church, BBCWhen atomic fuels are spent, it is separated into its component parts, one of the products is plutonium.

The gradual governments have placed the material to leave the option to recycle the material in the new nuclear fuel.

Storage of this highly radioactive material – in its current form – is expensive and difficult. It is often required to be canceled, as radiation damages the containers that are placed in it. And it is protected by armed police. The cost of all costs the taxpayer more than £ 70m per year.

The government has decided that the safest – the most economically viable solutions – to “stabilize” its entire plutonium stockpile.

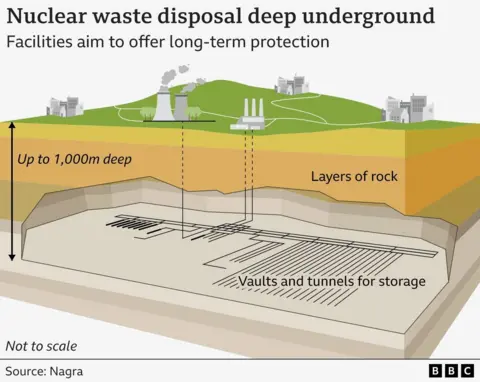

This means that a feature will be constructed in the cellfield where the plutonium can be converted into a stable, rock -like material, which can eventually be disposed of deep underground.

In a statement, Energy Minister Michael Shanx Said that the objective “was to keep this material beyond access, in a form that reduces long -term security and safety burden during both storage and ensures that it is suitable for disposal”.

Scientist of nuclear material from Sheffield University, Dr. Lewis Blackburn stated that the plutonium will be “converted into a ceramic material”, which is still radioactive, solid and stable, so it is considered safe to settle.

“The type of ceramic remains to be fixed (and selecting the right material) is a matter of ongoing research.”

Kevin Church, BBC

Kevin Church, BBCProfessor Clair Korchhill, a nuclear waste expert at Bristol University, said the government’s decision was a “positive step”.

He told the BBC News that it paved the way for the cost and danger of the plutonium storage in the Cellfield “by changing it and locking it into a solid, durable material that will last for millions of years in a geological settlement facility”.

“These materials are based on those that we find in nature – natural minerals, which we know is uranium for billions of years.”

The government is currently in the early stages of a long technical and political process of choosing a suitable site to build a deep geological facility that will eventually be the destination for the country’s most dangerous radioactive waste. This facility will not be operational by at least 2050.